Democracy Has Its Time and Place; Authoritarianism Needs No Second Invitation

- Selom Heymann

- Aug 11, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 11, 2024

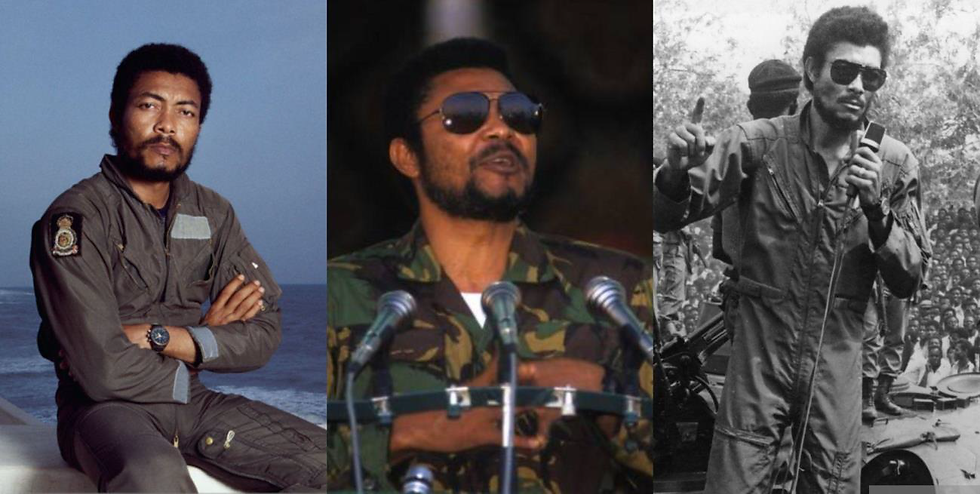

For what it’s worth, democracy is not all that bad, so surely there is justification to try and bring democracy to the developing world? It is a nice thought, an honourable sentiment at that, but history is unkind to us in this regard. Robert D. Kaplan emphasises that social stability results from the establishment of a middle class. However, it is authoritarian systems, including monarchies, which creates middle classes, and not democracies (Kaplan, 2018). As Kaplan deduces, authoritarian systems and monarchies which, having achieved a certain size and self-confidence, revolt against the very dictators who generated their prosperity (2018). To bring things close to home, I myself am a first-generation immigrant whose parents left a socially unstable situation back home in Ghana in the 80s. Back then Ghana, the first Sub-Saharan African colony to achieve sovereignty, was under the long-noted ruling of Jerry John Rawlings, who forcibly seized power from our very first president, Kwame Nkrumah. Both ran and led authoritarian regimes. Ghana functioned mostly as a one-party state, whilst effectively repressing civil society, and suppressing the media. Yet, it was through the rule of JJ Rawlings that our country stabilised, despite it being under a dictatorship. Not only that, but as Kaplan remarks, eventually, he had himself elected democratically (2018). But this came only after he stabilised our society, and facilitated the creation and improvement of reliable bureaucratic institutions.

See, it is an easy point to miss, and Kaplan takes care to highlight how foreign correspondents in sub-Saharan Africa miss this point, when they equate democracy with progress, ignoring both history and centuries of political philosophy (2018). But for many places, the choice is not between dictators and democrats. Far from it! The only choice is between bad dictators and slightly better ones (2018). Not exactly inspiring, but history unfortunately burdens us with harsh truths. As Kaplan succinctly surmises:

To force elections on such places may give us some instant gratification. But after a few months or years, a bunch of soldiers with grenades will get bored and greedy, and will easily topple their fledgling democracy. As likely as not, the democratic government will be composed of corrupt, bickering, ineffectual politicians whose weak rule never had an institutional base to start with: modern bureaucracies generally require high literacy rates over several generations (2018).

The above quote describes the current malaise of Mali to a tee, whom I will mention again shortly. Democracy is by no means the absence of tyranny to set the record straight (2018). Not even the absence of anarchy. The American Founding Fathers understood this so well, they created one of the most effective systems of checks and balances some two and a half centuries ago, that sought to create a stable and independent society of hard-working peoples, even at the expense of other people whom they deemed of lesser backgrounds, namely poor people (CUNY Graduate Center, 2019). Many of the founders, as Vanessa Williamson – a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution notes – did not want poor people to undermine their bosses through secret ballots, and thus disenfranchised them from democratic voting rights (2019). This is a rather curious paradox considering the fact that one of the, if not the most well-known verse from the United States Declaration of Independence, reads in part “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” So much for that huh?

Just to drive the point home, one only needs to look at democratic South Africa. News coverage from the Western World had celebrated it so much for its impressive attempts at coming to terms with the crimes of apartheid, that it long overshadowed the country’s growing problems. It was at the time of the Kaplan’s writing (in 1997), one of the most violent places on earth and this continues to be true even today. Unemployment is markedly rampant now, as it was back then, and educated people continue to flee (Kaplan, 2018). Mali, once seen as an exemplary symbol of democratic governance in sub-Saharan Africa by Western observers, barely even functions as a nation-state in my view nowadays by most accounts. The lesson here is, as Kaplan points out, is that states have never been formed by elections. “Geography, settlement patterns, the rise of literate bourgeoisie, and, tragically, ethnic cleansing have formed states” (2018). The history of the United States, from its very origins up until mid 1900s, coinciding with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, further underscores this statement. Democracy, summarized by Kaplan, rather often weakens states by “necessitating ineffectual compromises and fragile coalition governments in societies where bureaucratic institutions never functioned well to begin with” (2018). Because democracy neither forms states nor strengthens them initially, Kaplan takes the view that multi-party systems are best suited to nations that already have “efficient bureaucracies and a middle class that pays income tax, and where primary issues such as borders and power-sharing have already been resolved, leaving politicians free to bicker about the budget and other secondary matters” (2018).

References

CUNY Graduate Center (2019, June 06). Capitalism and Democracy: Can They Coexist? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXJfXweo1dM&t=1461s

Kaplan, R. D. (2018, May 29). Was Democracy Just a Moment? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1997/12/was- democracy-just-a-moment/306022/

Comments